Sleep Aids

Informed Choices: Sleep Aids and Products

Click through the available research on baby sleep aids and sleep products:

Throughout history, parents have used a wide range of items which they feel (or they are told) will benefit their babies’ sleep. In recent years products that are designed to ‘promote infant sleep’ have proliferated. Some of these products or sleep-aids have also become linked with increasing or decreasing babies’ risk of SIDS, or otherwise affecting babies’ health.

Is encouraging babies to sleep more deeply or for longer a good thing?

Many ‘sleep aids’ marketed to parents claim to make babies sleep more deeply and for longer. Parents should be wary of any ‘tips’, products, or ‘lifehacks’ that make these claims. Babies, especially newborns, have short sleep cycles and wake often during the night and the day. Although this can be tiring (because it is not the way that Western adults prefer to sleep!) it is good for babies’ development, and frequent waking is protective against SIDS (Ball, 2025). Waking from sleep, otherwise known as arousal, is an important survival response that helps babies to regulate breathing and other processes. Things that interfere with an infant’s arousability, especially during the critical period of development between 2-4 months, can increase the risk of SIDS (Horne, 2020).

Because of this, things that claim to help babies sleep deeper or longer can sometimes go against safe sleep guidance. Take time to think before using any ‘tips’ or ‘tricks’ that you might see online, and if you are not sure about something it is best to follow trusted safe sleep guidance. Avoid placing objects on your baby’s body that might compromise their ability to breathe, avoid products that excessively restrict your baby’s movement, and avoid using home-made replicas of fashionable products.

Product Safety

The UK’s Office for Product Safety and Standards published their guide to Child Safety Products in March 2025, launching a campaign about safety in regards to sleep products. Infant sleep products often have labels that say they comply with or exceed safety standards. However, these standards are usually designed to test general safety (such as sturdiness and flammability) and cannot accurately measure a risk of SIDS.

Products that rock and ‘shush’ babies attempt to recreate the experience of being held and soothed by a parent. However, they are not a substitute for parental vigilance / attention and many manufacturers’ instructions advise that they are used only with a caregiver present.

Side-Car Cribs, Bed-Side Cots, Co-Sleepers

Having your baby sleep in a cot or Moses basket in the same room as a care-giver, for all day-time and night-time sleeps, until they are six months old, is a key piece of the advice given to new parents for reducing the risk of SIDS.

Furniture Options

There are different types of furniture available that parents may use for keeping their babies close at night. Some parents place their baby to sleep in a standard cot, cradle or moses basket, located next to their bed or elsewhere in their bedroom. Other parents place their baby to sleep in a three-sided cot which is joined to the parents’ bed. This provides easy access to, and contact with, the baby, as well as a separate sleep surface. These are often known as side-car cribs or bed-side cots, and are sometimes known as ‘co-sleepers’ (especially in the US). In the UK bed-side cots are increasingly popular and there are now several different types available in a variety of sizes.

Safety Considerations

Different bed-side cots incorporate various features, but all have the facility to keep the baby close to a parent with no barrier to hinder night-time contact. A safe bed-side cot should fasten to the parents’ bed or have locking wheels to prevent it from being accidentally moved away from the bed while the baby is in the cot. There should be no gap between the cot/crib and the bed. It should also include a detachable or moveable 4th wall that can be secured in place if the baby is left to sleep in the crib alone. It is desirable if the height of the cot/crib can be adjusted to match the height of the adult bed.

Sometimes parents make their own side-car cribs by removing the side-wall of a standard cot and somehow fastening the cot to the adult bed. With the 4th side permanently removed from the cot it is not safe to leave babies unattended, and it can be difficult to adjust the height of the cot to match the height of the bed, leaving the potential for gaps in which a baby might get trapped.

Research Gap

To date, no research has investigated whether one type of cot helps with feeding or sleep more than another in the home. Marketing information and parents’ reviews indicate that 3-sided cots are popular with breastfeeding mothers, especially when they are recovering from c-section deliveries, or when their babies are small and feeding frequently at night. The research conducted on 3-sided cots has primarily examined their use in hospital post-natal wards, but a US study investigated the dangers and injuries obtained by infants using at-home co-sleepers. They concluded that when used appropriately they are just as safe or safer than any other type of cot/crib and accidents remain very low overall.

Understanding the Research

We provide the research and evolutionary theories behind our sleep aid content to help you understand and inform safe sleep practices with your infant. As a research-based site, BASIS prioritises bringing the research to you to inform your decisions. Click through to learn more below:

In UK hospitals, it is standard practice for babies to ‘room-in’ with their mothers on the postnatal ward. Typically babies sleep in a standard bassinette (a four-sided plastic box that sits in a metal frame with wheels. Some hospitals now also use side-car cribs (a three-sided bassinette that securely clamps onto the side of the mother’s hospital bed, or is atop a hydraulic stand that can be locked in place and tethered to the mother’s bed).

Side-car cribs are very popular with mothers following delivery as they are more easily able to see, touch, and pick up their babies from this location. Mothers recovering from episiotomies and caesarean incisions, who have limited mobility, find them particularly beneficial (Klingaman, 2009).

After a vaginal, unmedicated delivery, using a side-car crib on the postnatal ward helps mothers and babies to breastfeed more frequently, which contributes to increasing the overall duration of breastfeeding (Robinson, 2014). There is no difference in the total amount of sleep both mothers and babies get based on the type of cot they have on the postnatal ward (Tully and Ball, 2012).

A large randomised trial examining the general use of side-car cribs for all mothers and babies, regardless of delivery type, did not find an increase in long-term breastfeeding duration (Ball et al., 2011).

Several research studies have investigated the impact of infant sleep location on the postnatal ward (standard cot versus side-car crib) on breastfeeding outcomes. To date, research has found that following an unassisted, unmedicated vaginal delivery, infants assigned a side-car crib breastfed significantly more frequently whilst on the postnatal ward, and breastfed for longer after leaving hospital, compared to infants who were assigned a standard cot (Ball et al., 2006; Ball, 2008; Robinson, 2014).

These results have not, however, been replicated following deliveries where mothers received opioid labour analgesia or obstetric intervention (i.e. instrumental delivery and/or caesarean section delivery) (Ball et al. 2011; Tully and Ball 2012). The World Health Organisation (2009) recommend having one’s infant easily accessible postpartum. This is supported by Tully et al. (2014), adding that this is not successfully accomplished in stand-alone cots, suggesting side-car cribs as the optimal strategy.

No studies have found any evidence that side-car cots pose any risk to babies. One study (Tully and Ball, 2012) suggested that following a caesarean section delivery, the height and angle of a standard cot posed several potential risks to infants whose mother’s movements were impaired as a result of the caesarean section procedure. The observed risks associated with the standard cot after caesarean section delivery included mothers lifting the infant without supporting their head, tipping the cot whist attempting to place the infant within it, dropping the infant into the cot and prone infant sleep. An American Academy of Pediatrics report on Safe Sleep and Skin to Skin Contact in the Neonatal Period highlighted the potential of side-car cribs for enhancing infant safety on the postnatal unit (Feldman-Winter et al 2016).

Thompson and Moon (2016) investigated the dangers and injuries obtained by infants using at-home co-sleepers. They concluded that when used appropriately they are just as safe or safer than any other type of cot/crib and accidents remain very low overall.

Research has found that bed-sharing can be associated with a baby experiencing an increased chance of SIDS or accidental death in particular circumstances. These are a) If you smoke (or smoked in pregnancy), b) have recently drunk alcohol, or taken drugs or medications that make you sleepy or sleep more heavily than normal, and c) your baby was born prematurely or with low birth-weight. Read more at safe sleep guidance.

In these circumstances, side-car cots may provide a safer alternative to bed-sharing, and provide easy access for comforting and feeding your baby during the night.

Regardless of mode of delivery, mothers have expressed an overwhelming enthusiasm and preference for side-car cribs whilst on the postnatal ward (Tully and Ball, 2012; Tully et al., 2014). Mothers stated that side-car cribs, unlike standard cots, permitted visual and physical access to their infants; enabled emotional closeness; facilitated breastfeeding; allowed them to settle their infant quickly; and minimised calls to postnatal ward staff.

Following a caesarean section, mothers commented unfavourably about standard cots compared to side-car crib use (Tully and Ball, 2012; Tully et al., 2014). Furthermore, side-car cribs can play an important role in promoting mother-infant contact and successful breastfeeding initiation amongst these dyads (Tully et al., 2014). This is significant, as this method of non-labour induced delivery tends to result in lower rates of breastfeeding overall due to inhibited lactation and physical pain.

Similar findings were reported following an audit of different cot-types trialled on Belgian postnatal wards which led to some hospitals adopting a practice of exclusively using side-car cribs on the post-natal ward (wooden variety, see picture below right, which are different in design to those commonly used in UK). (Martine van Haver, Midwife, Lueven, pers comm 2012).

Hammocks and Swings

Hammocks

Baby hammocks or sarong cradles offer a form of co-sleeping that is traditional in many cultures, particularly South-East Asia. A recent randomised trial from New Zealand investigating the use of hammocks for infants (Chiu et al 2014) found that babies sleeping in correctly used hammocks are as safe as babies sleeping in a cot, as long as the babies are not swaddled and cannot roll over yet. This study also found that babies in hammocks sleep deeper, but for less time than those in cots.

Baby hammocks are now available that stretch over the top of a conventional cot or crib. As with many other infant sleep products, advertising claims that using a hammock ‘helps reduce risk of SIDS’ and the risk of ‘flat head syndrome’, there is no research to support either of these claims. When used with small babies, these devices may cause the infant’s head to tilt forwards pushing their chin on their chest which can cause dangerous obstructions of the infant’s airway.

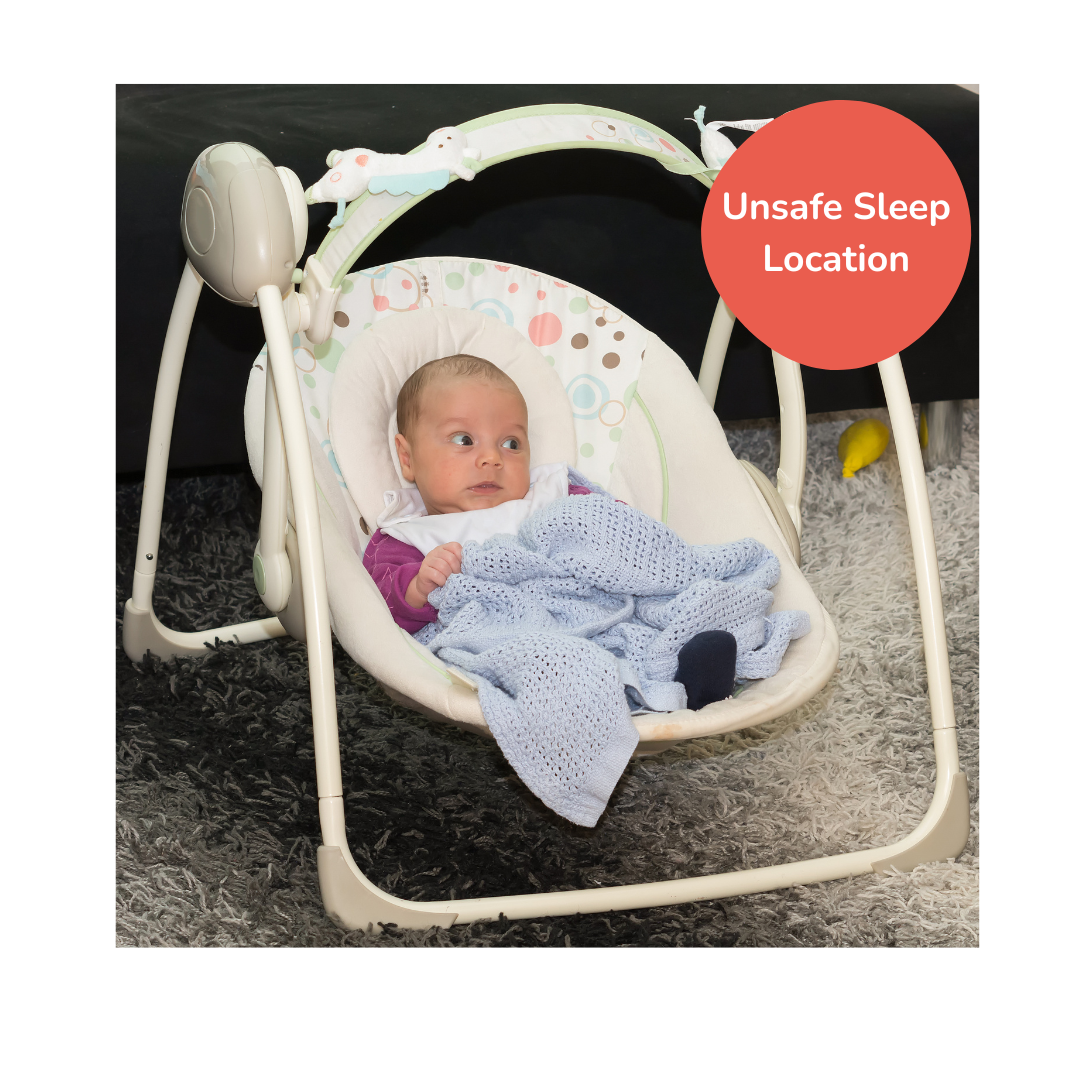

Swings

Several types of baby swings and swinging cradles are marketed as sleep spaces. However, it is not safe for babies to sleep in swing seats (or baby bouncers) of any kind, nor to be left in them unattended. Small babies in swings can find it difficult to hold up their heads or slip from the restraints into a position where their breathing gets obstructed. Should a baby fall asleep in a swing they should be moved to a flat sleep surface to sleep on their back. Certain types of rocking infant sleeping products have been recalled and removed from the US market due to infant deaths, however similar products can still be purchased internationally.

Sleep by Swaddling and Soothers

Baby Sleep Bags

Baby sleeping bags are now very popular with parents, and are promoted as a way of reducing the risk of SIDS

In the UK and elsewhere, studies have shown that overheating increases the risk of SIDS compared to babies sleeping at cooler temperatures (Ponsonby et al. 1992). Baby sleep bags are recommended to help avoid overheating.

The main reason is that baby sleep bags are intended to prevent babies from getting their heads covered with loose bedding during sleep. For this reason it is important to ensure babies are not placed in sleeping bags that are too big, and that they could slide down in to. Many parents feel sleep bags help babies sleep better, by preventing them from wriggling out of bedding or kicking off blankets, and keeping them at a comfortable temperature (L’Hoir et al. 1998).

No research has yet examined how baby sleeping bags are actually used, and whether parents use blankets in addition to sleep bags. The UK’s biggest SIDS research and advisory body, the Lullaby Trust, recommends the use of baby sleep bags, but emphasises that these should be well-fitting around the babies arms (to prevent the baby from sliding inside the bag) and that parents should choose bags with the appropriate tog rating for the temperature of the room the baby is sleeping in.

Swaddling (firm wrapping in a cloth or blanket) is an ancient and widely-used baby-care tool.

Some research studies have found that swaddling can help calm and soothe babies, and help them sleep. Researchers have suggested that swaddling can help babies settle on their backs, and prevent them turning on to their front or getting their heads covered by bedding. Parents in Western countries are increasingly turning to swaddling to help calm their babies for sleep.

Recently, however, some research has suggested that swaddling might not always be safe: Babies that are swaddled may sleep more deeply. While this may at first appear to be a good thing it may in fact put them at higher risk of SIDS. The ability to arouse (begin to wake) from sleep is key to a baby’s ability to cope with things in their environment that might otherwise put them at risk of SIDS. Research shows that swaddling reduces this ability much more among babies for whom swaddling is a new experience – i.e. have NOT been swaddled since birth. A review paper found that swaddling increased SIDS risk if the baby was on its front, and decreased it for babies sleeping on their back (Van Sleuwen et al., 2007). However a recent UK study found an increased risk of SIDS for all swaddled babies – including those sleeping on their back (Blair et al., 2009). The current evidence is therefore contradictory.

Swaddling can also put babies at higher risk of bone-development problems, chest infections and overheating. It is also not considered to be a good idea to swaddle a baby when bed-sharing. Babies need to be able to use their arms and legs to alert adults who get too close, and to move covers from their faces. Swaddling prevents a bed-sharing baby from doing this. A review of swaddling also suggested that swaddling may negatively impact breastfeeding by reducing feeding frequency, and thus it may disrupt maternal milk production (Dixley and Ball, 2023).

If you decide to swaddle…

- Wrap firmly but not too tightly.

- Baby’s legs and feet should be able to move freely, and bend at the hip.

- Leave arms free for babies over 3 months.

- Leave baby’s head uncovered, and don’t let baby get too hot.

- If you bring baby into your bed, remove swaddling to prevent overheating.

- Always place baby to sleep on their back.

If you are going to swaddle, evidence suggests it is safest to do it from birth. Don’t suddenly start when SIDS risk is highest (at 2-3 months).

For more information on swaddling, and swaddling methods, the NCT, AAP, ISPID and Red Nose (Australia) all provide useful information.

Dummies, Soothers, Pacifiers

Dummies (also known as pacifiers or soothers) have long been used by parents who feel they help soothe or settle their baby. In some countries, namely the US, pacifiers are recommended as a SIDS reduction measure for all babies, however, this is not the case in the UK. Studies in the UK and Ireland have identified that babies who normally have a dummy and are without it on a particular night have an increased risk of SIDS while babies who never use a dummy do not have an increased risk of SIDS (McGarvey et al., 2003).

Understanding the Research

We provide the research and evolutionary theories behind our sleep aid content to help you understand and inform safe sleep practices with your infant. As a research-based site, BASIS prioritises bringing the research to you to inform your decisions. Click through to learn more below

Dummies, also known as pacifiers, have been associated with a reduced risk of Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS) in numerous studies since the early 1990s. Research from the United States (Li et al., 2006; Moon et al., 2012), the UK (Fleming et al., 1999), and other regions worldwide has consistently found that dummy use is associated with a lower risk of SIDS. However, more recent UK research (Blair et al., 2009) found that this association may now be less significant, possibly due to improved overall infant care practices. Despite this, some health authorities recommend considering the use of a dummy when settling a baby to sleep because of its potential protective effect. The exact reason why dummies might reduce SIDS risk is still unclear, but proposed explanations include physical mechanisms (e.g., preventing the baby from turning their face into bedding or encouraging lighter sleep) and behavioural factors (e.g., parents who use dummies may also engage in other protective behaviours like room-sharing). Notably, some studies have shown that the increased risk of SIDS was specific to babies who usually used a dummy but slept without one (McGarvey et al., 2003), suggesting consistency in dummy use is important.

Research has shown that sucking (e.g. breastfeeding, finger-sucking or dummy use) has a calming and soothing effect on babies, including a reduced response to pain (Victoria et al., 1997). Dummies can help calm babies, reduce crying, and encourage sleeping (Righard and Alade, 1997).

Studies have shown that dummy use can have unwanted effects. Some, e.g. Fleming et al., 1999 have found that dummy use can lead to less breastfeeding and earlier weaning from the breast. A review of research (Jaafar et al., 2012) found dummies did not cause mothers to stop breastfeeding earlier (up to when their babies were 4 months old) when they were very motivated to breastfeed. However they were not able to say whether or not less motivated mothers might be disadvantaged by dummy use.

Breastfeeding in itself reduces the risk of SIDS, along with other diseases, and helps with mother-baby bonding (Thompson et al., 2017).

Some research has found links between dummy use and tummy and chest infections, and recurrent infections of the middle ear, but the exact relationship betwee dummy use and infections is not yet clear (North et al., 1999) and recurrent infections of the middle-ear (Rovers et al., 2008).

Slings and Baby-Wearing

Around the world, babies are carried by their mothers (and fathers, siblings and community members) throughout the day. These babies spend their days sleeping in a sling, which is usually made from a simple piece of cloth. In the UK and US, the practice of carrying a baby in a sling or soft baby carrier is known as ‘baby wearing’. It’s less common for parents in the UK to use a sling for their babies’ daytime sleep but there are many reasons why this may be helpful. See the ‘TICKS’ guidance:

Understanding the Research

We provide the research and evolutionary theories behind our sleep aid content to help you understand and inform safe sleep practices with your infant. As a research-based site, BASIS prioritises bringing the research to you to inform your decisions. Click through to learn more below

Babies born prematurely who are carried (in skin-to-skin contact) by their parents have improved temperature regulation, increased oxygen saturation and, over time, better growth (Bastani et al., 2017). The World Health Organisation supports 24 hour a day baby wearing for premature babies, until they reach their full gestational age, especially where modern medical care is unavailable to parents (WHO, 2012). While most parents won’t need to consider wearing their babies in direct skin contact, or 24/7, this should offer some reassurance that wearing a baby can be safe and beneficial, even during a long daytime nap.

Following some simple guidelines will help you to keep your baby safe in a sling. As with any item of baby equipment, you may want to take some time to practise using a sling or baby carrier, perhaps with another adult watching you. Be sure to follow the manufacturers’ instructions for safe use of any sling, carrier or other equipment. Carefully check any sling or baby carrier that you own, buy or borrow for wear and tear. Only undertake safe activities while your child is in the sling or baby carrier – no jogging, cycling or extreme sports!

Be careful in selecting your sling, carrier or other equipment. Some ‘bag style’ slings are shaped in a way that leads to the baby curling up in the sling, pressing their chin towards the chest.

Further safety information and details of TICKS are available on the School of Babywearing Website and at Which? (Consumers’ Association). Carrying Matters is a comprehensive resource for caregivers to learn about babywearing and how do it safely.

For information about the different types of sling available, visit www.babywearing.co.uk, or find a sling meet, group or library or a Babywearing Consultant near you on their information pages.

What are the benefits?

Carrying your baby in a sling while they sleep may benefit them, while also allowing you to have your hands free. Little research has looked specifically at the benefits of carrying babies in a sling while they sleep. However research in related areas suggests that keeping close contact may have benefits for both mother and baby (Horne, 2020).

The advice for new parents is that your baby should sleep in the same room as you, day and night, until they are at least 6 months old. Studies have shown this to reduce the risk of SIDS. An English study, comparing 325 SIDS babies with 1300 control babies, found that 75% of the day-time SIDS deaths occurred while babies were alone in a room. Using a sling or baby carrier may make it easier for you to keep your baby close during the day.

Research looking at newborn babies has shown that close contact helps them to sleep more quietly and for longer (Morgan et al., 2011; Anisfeld et al., 1990). They can hear your heartbeat, feel your movements and be reassured that you are close, and will not feel the stress of being separated from you. When your baby starts to stir, you will be immediately aware of it if you are wearing them. You can pick up on their feeding cues more easily and breast milk production is improved when you keep your baby close to you (Furman et al., 2002; Brooks and Anderson, 2008). Some research shows that mothers who hold their babies feel calmer, and less anxious, and show less cortisol reaction to stress (Heinrichs et al., 2001).

Parents who formula feed may find that wearing their baby helps them to bond and, for Dads and partners, baby wearing may allow you to take your baby for a walk, giving your partner some time to themselves.

Sometimes parents are worried that babies who settle to sleep in a sling or baby carrier may be less likely to settle on their own.

Parental experience highlights that there is huge variability in babies’ sleep preferences. While some babies settle better when they sleep in a cot alone, others find it difficult to settle if put down for sleep alone. Studies show that babies need to have positive sleep associations and that babies whose sleep environment is calm, and for whom going to sleep is pleasant, will develop better long-term sleeping habits (Bathory and Tomopoulos, 2017). For some babies a calm and pleasant sleep environment involves being in contact with their mother or other caregiver – a typical practice in many countries. Some babies therefore prefer to settle by being soothed by their parents, and not by being left alone, so these babies fall asleep happily in a sling. Some slings are easy to take off if your baby falls asleep at night time and you want to take the sling off without disturbing them. Sometimes parents choose to wear their babies until they fall asleep and then lie them down.

Electronic Infant Sleep Devices (Monitors)

Technological developments now allow you to monitor many aspects of your baby’s physiology from respiratory rate to temperature to heart rate to blood oxygenation and more.

Infant electronic sleep devices are a relatively new market. Companies offer increasingly smart and wearable devices designed for monitoring babies’ physical data or changing their sleep environment. The devices are aimed at increasing uninterrupted sleep or reassuring parents of their infant’s safety. They may also bring a false sense of security which could result in less attention to the baby and a higher SIDS risk (Ball and Keegan, 2022).

What sorts of devices are out there?

Infant Sleep Machines

Infant sleep machines (ISMs) or noise machines produce an ambient sound to disguise background sound in the infant’s sleep environment and promise longer and deeper sleep. Whether or not this works, research has found that ISMs are capable of reaching sound levels that can damage infant hearing and auditory development (Hugh et al., 2014). These devices can also disturb parent’s ability to sleep, prompting parents to prematurely relocate infants into a separate room (Ball and Keegan, 2022). However responsible use of these machines and following manufacturer guidelines eliminates this risk. Some cry sensors and sound machines have AI capabilities built into bassinets and are marketed as ‘virtual babysitters’ where the devices respond to infant activity by rocking, vibrating, or prompting soothing sounds to be played (Ball and Keegan, 2022). While these devices support reduced caretaker-infant interactions, these devices have not yet been researched to assess potential impacts on breastfeeding outcomes and infant social development (Ball and Keegan, 2022).

Audio and Video Monitors

Audio and video monitors are usually used to relay infant cries and breathing noises. In these respects the technology is effective, but may mean you are more comfortable to leave your baby in a room on their own, which is a SIDS risk factor. The benefits of close contact with their parents for babies cannot be replaced by baby monitors. Overall, however, there is little research on the effects of using baby monitors (Ball and Keegan, 2022). Some parents find that digital monitoring their infant actually increases their anxiety given their ability to compulsively observe their infant (Jewitt et al., 2021).

As with any technological device, the potential remains for the battery to run out or power source to fail.

Biological Monitors

Biological monitors can report on a wide range of infant physiological measurements, but the most common ones are monitoring breathing and heart rate. These monitors come in different shapes and sizes. Some are even wearable, for example as socks or gowns. Studies indicate that biological monitors likely do not help prevent SIDS in healthy term infants. However, they may be helpful for vulnerable babies, for example preterm infants. They may also be used for babies who have undergone heart surgeries or who have been diagnosed with respiratory problems. It is recommended you consult a medical practitioner for advice if you are considering using a biological monitor on your baby.

Baby Boxes vs Sleep Nests and Pods

What are baby boxes? Where are they used today?

New parents in a variety of locations will nowadays receive a Baby Box around the time their baby is born. All baby boxes consist of a mattress and a fitted sheet that will allow the box to be used as an infant sleep space within usually a plastic or cardboard box. In some locations (Finland, Scotland), Baby Boxes are given out as a gift from the Government to new parents, and they are packed full of useful items for the baby’s first year of life (Skea et al., 2022). In other locations, Baby Boxes are being given out by NHS Trusts and Local Authorities as part of infant safe sleep education (Bally and Taylor, 2020). Similarly, a team in New Zealand have promoted a wahakura, a Māori innovation based on traditional baskets handwoven from flax, as a tool for parents to use in their bed as a safe sleep location for their infant. Following the earthquake in Christchurch, New Zealand, emergency bedding for newborns was located in the form of a plastic box with a mattress insert, referred to as a Pēpi-Pod® (pēpi being the Maori term for baby). Subsequently the New Zealand government piloted the Pēpi-Pod® programme which consists of both providing parents a Pēpi-Pod®, i.e. plastic baby box, as well as infant care education (Ball et al., 2021). This culturally-targeted safe sleep enabler for indigenous communities contributed to a drop in SIDS, particularly in Maori communities (Ball et al., 2021; The Pēpi-Pod® Program, 2022).

Additionally, several major retailers and other specialist companies are producing retail versions of Baby Boxes designed to be purchased as gifts for new families, full of premium products (Ball and Taylor, 2020).

It can be useful to have a portable sleep space such as a cardboard Baby Box for use during the day, or if you are sleeping away from home. If you do not have access to a Moses basket or cot it is safer for your baby to sleep in a box than in a car seat or on a sofa.

Baby Box Safety Considerations

Be sure to use your Baby Box safely and follow the manufacturer’s or distributor’s instructions. Do not place a Baby Box on a high or precarious surface where it (and your baby) might fall. Do not use it to carry your baby, or place near a heat source. Baby boxes are not safe for transporting babies in cars or other vehicles.

All baby box mattresses should carry a permanent label stating that they comply with UK and EU regulations, including fire safety. Do not use a mattress that does not have this label. Always place your baby on their back in the box and keep the box free from toys and excessive bedding. Stop using the box as soon as your baby begins trying to roll over.

The Lullaby Trust (UK SIDS Charity) has issued a statement about the safety of Baby Boxes that can be found on their website as you scroll down.

As with all infant sleep spaces, Baby Boxes should be used with common sense and safe sleep guidance should still be followed.

Co-sleeping nests and pods

There is an expanding market of nests and pods being marketed for use in the parental bed, with the intention that they will keep babies securely in one place and, by the use of padded sides, prevent parents from overlying the baby. While there is merit in the idea of providing the baby with a safe space within the parents’ bed (as per the New Zealand Pepi-Pod and Wahakura programmes), pods and nests designed for bed-sharing can be problematic and are not the same as baby boxes (Ball, 2025). Many parents who purchase or are gifted these sleep nests or pods for their infant to sleep in, but upon reading the manufacturers instructions it is often revealed that these products are intended for when the infant is both awake and supervised and not recommended as a sleep location (Ball, 2025).

Nest and Pod Sleep Safety

One key component of safer sleep guidance is to keep the baby’s sleep space clear and flat; clear from pillows, cushions, bumpers, soft toys etc, and flat rather than inclined, saggy, or squishy. Soft and squishy items in the sleep space create two hazards for babies:

- they can block a baby’s nose and mouth and make breathing difficult or impossible

- they can insulate a baby’s head and prevent them from loosing heat leading to overheating

The physiological stresses of overheating via head covering or struggling to breathe via airway covering are both associated with SIDS, while airway covering can also lead to suffocation.

Placing babies to sleep in pods/nests that surround them with a squishy cushion-like barrier made of insulating material therefore contradicts these aspects of safer sleep guidance (Ball, 2025). It is also why Pepi-pods and Wakahura have rigid sides with no padding.

In our infant sleep research we have found pods and nests are very popular with parents who feel their baby sleeps well (longer, or more deeply) when place in one of these products, and parents often place pods/nests inside their baby’s cot to make it feel more comfortable and cosy.

But it is important to remember that prolonged and deep sleep in early infancy is also associated with an increased chance of SIDS — when babies sleep deeply they fail to arouse to face covering and other physiological challenges. In early infancy it is normal for babies to spend most of their sleep time in the lighter phases of sleep, and to arouse frequently.

If you have bought or been given a baby nest or pod it is safest to only use it when your baby is awake, and to ensure they sleep on a flat clear surface away from any pillows, soft toys etc.

If you are unwilling/unable to place your baby on a safer surface for sleep, then avoid leaving your baby alone while asleep in the nest/pod. Be sure they are in the same room as a carer who is watching them and checking on their safety.

Using a pod/nest while bed-sharing / co-sleeping is not necessary and can introduce an additional hazard to the sleep environment. If you are planning to bed-share (or even if you aren’t, as bed-sharing can happen by accident) baby-proof your bed to give your baby a clear flat surface to sleep on next to you. See this information from Lullaby Trust on preparing your bed for safer bed-sharing.

Last Reviewed: July 2025