What are SUDI and SIDS?

Here we explore the nuances between SUDI and SIDS.

Here we explore the nuances between SUDI and SIDS.

Read the guidelines on infant sleep safety as well as the research behind this advice.

Breastfeeding has a soporific (sleepy) effect on you and your baby. Learn about sleep safety when breastfeeding.

Learn about prevention of AHT in babies, also referred to as traumatic head injury.

Taking care of your baby often results in sleep disruption and parental fatigue, which can be linked with postpartum depression.

The relationship between infant sleep environments and sudden unexplained death in infancy (SUDI) for instance, has been the subject of hundreds of studies. Comparatively, minimal research has sought to understand the infant health consequences of the various forms of sleep training currently being employed and recommended.

Issues affecting infant survival include unexplained mortality (SIDS), accidental deaths, and deaths from injuries that are violently inflicted (traumatic head injuries). Sleeplessness, inconsolable crying, and colic are all issues that trigger parental frustration, and may increase the risk of post-natal depression, both of which are compounded by parental sleep disruption, and may lead not only to rare instances of inflicted brain trauma, but also to accidental deaths resulting from ill-considered sleep locations, and failure to be alert to SIDS risks.

On this page we cover some of the most common issues where sleep and safety intersect for parents and babies — however, we do not cover clinical sleep problems and a qualified health professional should be consulted for such guidance.

All new parents should receive information about SIDS and SUDI before or just after their baby is born. SIDS refers to Sudden Unexplainable Infant Deaths, and is grouped with other sudden explainable infant mortality under the heading Sudden Unexpected Death in Infancy (SUDI). Nowadays SIDS and SUDI tend to occur in similar circumstances, where families are facing multiple challenges, and an unexpected occurrence means the family are ‘out of routine’ on the night when the death occurs. In recent years, SIDS and SUDI nowadays often reflect situations where babies are exposed to multiple modifiable risk factors, but parents are unable to reduce risks by themselves and need support to do so.

If you are a parent who is reading this site, we assume this means you are looking for information and want to make informed decisions. This is what we aim to provide, at least for those topics where there is good research evidence about normal infant sleep.

Where little or no research exists, we’ll tell you — but if you are looking for information we don’t seem to provide let us know, and we’ll try to address that.

One risk that is common in many SUDI and SIDS cases nowadays is hazardous co-sleeping (for example sharing a bed, sofa, armchair or other surface with a baby for sleep after drinking alcohol or taking drugs). Although most new parents think that they will never sleep with their baby, research shows that many do so for various reasons (see the Lullaby Trust’s recent survey). In addition to the increased risk of SIDS that is associated with bed-sharing with a smoker (or being smoke-exposed during pregnancy), or with a recent alcohol or drug user, there is also a risk of accidents when adults sleep on an unsafe surface with a baby. To reduce the chance of these preventable deaths it is important for all parents and carers to be informed about co-sleeping and bed-sharing safety, whether or not they intend to co-sleep, as we all sometimes fall asleep with our babies when we don’t mean to – especially during night-time feeds. The information BASIS provides is to help minimise risk, in line with UK guidance that acknowledges that safer bed-sharing is a normal part of coping with night-time infant care.

See the UK guidance on safe sleeping below and click on each statement to learn about the research-backed reasons behind the guidance:

Explore our resources and information from the Lullaby Trust and the NHS about SIDS safety:

We provide the research evidence behind SIDS and SUDI risks to help you understand and inform safe sleep practices with your infant. As a research-based site, BASIS prioritises bringing the research to you to inform your decisions. Click through to learn more below:

Recently proposed by Herbert Renz-Polster and colleagues, the evolutionary-developmental theory of SIDS considers that a baby’s vulnerability to SIDS could reflect an imbalance between the baby’s current physiological demands and their current protective abilities (2024). Within this framework, SIDS is considered a developmental condition that occurs between when neonatal reflexes have stopped post-birth and self-protection abilities haven’t yet fully developed.

What does that mean for SIDS and sleep safety? Renz-Polster and the co-authors suggest that considering both the risk factors associated with SIDS as well as the protective resources that infants develop in supportive environments could prove helpful when considering sleep safety. Rather than only an avoidance of risk, this model suggests that babies’ developmental resilience can be supported by experiencing protective skills associated with biologically typical behaviours such as breastfeeding and bed-sharing (Ball, 2025).

For parent readers, this model informs how BASIS offers information both on risks to avoid (such as the sleep safety guidance above) as well as how some behaviours could be protective (learn more on our normal baby sleep development pages).

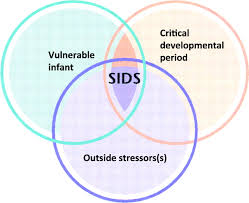

The Triple Risk Model is the original and most widely accepted model proposed to consider factors that could contribute to an infant’s risk of SIDS (Filiano and Kinney, 1994). As the name implies, there are three considerations that together indicate a high risk of SIDS: a vulnerable infant, a critical developmental period, and an external stressor.

The critical developmental period for most infants appears to be 2-4 months of age. This is when most SIDS deaths occur. No research can yet definitively state when infants born prematurely will experience the critical developmental period, nor when infants have moved through this period.

Infant vulnerability can arise from reasons such as asphyxia (insufficient oxygen for baby during birth), brainstem abnormalities, prematurity or low birth weight, or smoke exposure during gestation. There are some intrinsic factors of infants (characteristics they are born with) that may make them more vulnerable than others to SIDS, some of these vulnerabilities will be known by parents (low birth weight as one such example) and other potential vulnerabilities might not be known (genetic predisposition, cardiac condition, or brainstem anomaly for example). Thus SIDS guidance is offered to all families, and while the risk of SIDS/SUDI is very slim, preventative measures can still be taken by all families (Ball, 2025).

Sleeping position, head covering, overheating, post-natal smoke exposure, formula feeding, sleeping in a room alone, soft bedding, bed-sharing, or soft toys are all examples of potential risks for SIDS (Ball, 2025).

Although studies demonstrated a strong association between prone (on front) sleep and SIDS, and encouraging parents to sleep their infants in a supine position was associated with a dramatic fall in the SIDS-rate wherever such recommendations were introduced, we still do not know what it is about prone sleep that increases a baby’s chances of dying suddenly and unexpectedly. Various explanations such as toxic mattress gases and rebreathing exhaled carbon dioxide have been investigated and debunked. One potential finding relates to sleep patterns — babies experience more deep sleep and fewer spontaneous arousals in the prone position: it may be that some babies’ brains are not well enough developed to arouse themselves from particularly deep sleep when confronted with a physiological stressor, such as head covering.

While SIDS rates have lowered in recent decades, this universal reduction hides inequity in certain subpopulations. For example, in the US, African American, Alaskan Native, and Native American communities are disproportionately affected by SIDS (NICHD, 2001), and recently a higher incidence of SIDS in child-care settings has been identified (Moon, et al., 2008). In New Zealand, SIDS-risk is substantially higher in Maori families (Mitchell et al. 1993), but not those of Pacific Island origin (Scragg et al., 1995; Schluter et al., 2007). UK immigrants from ‘New Commonwealth’ countries (India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Caribbean) have a greatly reduced risk of SIDS compared with the White British population (Balarajan et al., 1989; Davies and Gantley, 1994; ONS, 2000), while in Holland infants of Moroccan immigrants have a SIDS-risk three-times lower than the Dutch population but infants of Turkish immigrants exhibit a significantly increased SIDS-risk (van Sleuwen et al., 2003).

This data underscores how socio-economic disparities – such as access to antenatal and postnatal care – as well as cultural practices contribute to safe sleep outcomes.

Professor Helen Ball’s work with Dr Eduardo Moya and the ‘Born in Bradford’ team exemplifies this cultural nuance. Local Bradford data established that white British families had a SIDS rate four times greater than the South Asian families, despite the fact that the South Asian families bed-shared (Ball et al., 2012). Their research found that South Asian infant-care practices protected babies from the key SIDS risks of smoking, alcohol consumption, sofa-sharing, absence of breastfeeding, and solitary sleep, contributing to the lower rates of SIDs in the community.

An article published in British Medical Journal in May 2025 discusses how social determinants (such as socio-economic status and health literacy) must be considered in SIDS risk reduction messaging.

Risk minimisation is an approach in SIDS and SUDI prevention that aims to reduce infant deaths by informing parents about infant care practices that invite risk in certain contexts to promote parents making informed choices given their own particular lifestyle and resources (Ball, 2025). This is the approach that BASIS adopts, and why each guideline is contextualised by research.

Risk elimination, as the name suggests, is the approach that aims to reduce infant deaths by instructing parents to eliminate infant care practices such as bed-sharing and prone sleeping, as advocated by the US Academy of Pediatrics (Ball, 2025).

The chances are that if you are breastfeeding you will lie down at night to feed your baby and you may accidentally fall asleep, even if you don’t intend to bed-share. It is therefore useful to think about how to make your bed as safe as possible for your baby BEFORE this happens. So make sure you always place your baby on a clear flat surface – not propped up on any pillows or bed-covers. Make sure pillows and bed-clothes are well away from your baby’s face and head. Make sure there are no gaps around the bed or between the mattress and headboard that your baby could get wedged or trapped in. Make sure you position yourself between your baby and other children, pets, and heavy-sleeping adults. Ideally there should be no children, pets or unaware adults in the bed with you and your baby.

Most breastfeeding mothers naturally sleep facing their baby with knees drawn up under baby’s feet and arm above baby’s head. This protects your baby from moving down under the covers or up under the pillow. Your baby should not be overdressed and covers must not overheat baby or cover his head.

Your baby may lie on her back or side to breastfeed. When putting your baby down to sleep, always put her on her back, not on her front or side.

If you have never breastfed and do not naturally sleep in this position with your baby, then consider sleeping baby in a cot in your room. Three-sided ‘bed-side’ cots are available which attach to your bed and may make night-time feeds easier while giving baby their own sleep surface.

Coping with a baby who cries inconsolably for prolonged periods can be extremely frustrating, particularly when you are tired and have no one to help. Such situations can often occur at night. This phenomenon is also referred to as Traumatic Head Injuries.

Babies most at risk are between 3-8 months of age. Traumatic Head Injury or Abusive Head Trauma (AHT) often causes irreversible damage. In the worst cases, children die due to their injuries.

Children who survive may have:

Even in milder cases, in which babies appear normal immediately after the abuse, they may eventually develop one or more of these problems (Golden and Maliawan, 2005).

Tip: If you ever find yourself in a situation where you feel you may harm a baby out of frustration or desperation, put the baby in a safe place such as a cot or pram, take a break, and ask another adult to take care of the baby for a while (Ball, 2025). Seek support, such as from ICON, a website offering help on how to cope with infant crying.

Sleep disruption is a predictable and normal part of learning to care for your baby (Ball, 2025). This disruption, while normal, can have serious consequences for parents health and well-being, with subsequent potential implications for their baby’s wellbeing (Ball, 2025). That is why we discuss parental sleep disruption under safe sleep – hoping to inform parents that their experiences are normal and provide reassuring research-backed information to help promote parent and infant sleep and health. The comparison of sleep duration between mothers of babies fed human milk, and those fed infant formula is particularly subject to myths.

New mother’s postpartum sleep has been found to be shorter in duration, more fragmented, less efficient with a greater proportion of time in bed spent awake, with mothers reporting greater sleepiness and fatigue (Newland et al., 2016). Sleep patterns change most dramatically for all mothers following the birth of their first baby — much more so than following any later births (Dørheim et al., 2009).

Clinically diagnosed post-partum depression affects up to 20% of UK parents in the year following birth and up to 50% more experience mild to moderate symptoms (Paulson and Bazemore, 2010). The issue of dealing with sleep disruption can adversely influence parental mental health, physical health, and emotional stability (Rudzik and Ball, 2016; Ball, 2025).

Learn more about normal baby sleep:

We provide the research on infant-related sleep disruption to help you understand and inform safe sleep practices with your baby. As a research-based site, BASIS prioritises bringing the research to you to inform your decisions. Click through to learn more below:

Last Reviewed: July 2025